Astronauts must be healthy. Job requirements. To avoid illness and mission failure, they quarantine before launch. They work and live in antiseptic conditions overhead.

Some suffer viral flareups or rashes in space. “Why is it that they get infections up there?” wondered University of Ottawa molecular scientist Odette Laneuville.

Laneuville and her colleagues indicate in a Frontiers in Immunology research that 100 immune-related genes, which promote opportunistic infections, may be lowered in activity.

Experts think understanding what makes astronauts more susceptible to infections might make space flights safer and enhance immunocompromised treatment on Earth.

Laneuville adds our bodies harbor many viruses and bacteria.

“And because we’re healthy, we keep those at check and dormant,” she explains. However, stress and immune system dysregulation can induce infections. Laneuville suspected something in space was changing the gene activity of astronaut blood immune cells, permitting these opportunistic infections.

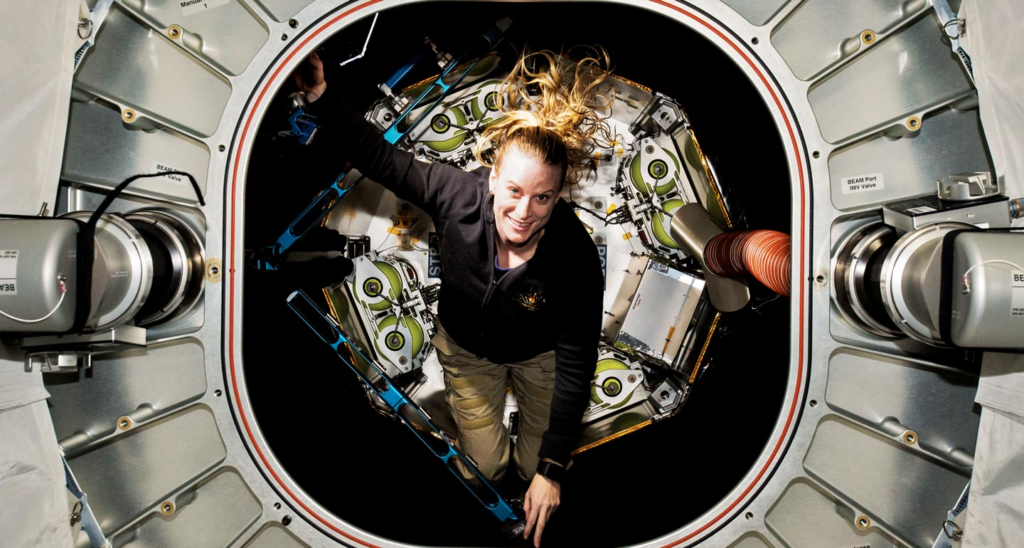

She and her colleagues recruited 14 American and Canadian astronauts to spend several months on the International Space Station at different dates. Laneuville had their blood taken before and after their missions on Earth and in space. The 10-minute land operation took 90 minutes in orbit.

They must carefully remove needles, tubing, and other equipment. Laneuville says they must safeguard everything. “No leaks. No blood. Otherwise, it will float and poison everyone.

The astronauts spun the blood and kept it in a super-cold freezer until they returned to Earth with samples. “I had to hire someone to process those,” she adds. “No, they’re too precious,” I said. Space blood. My infant needed care.”

The samples were collected over five years on various International Space Station trips. Laneuville advises patience. It’s worth waiting. I would have waited longer.”

This rare blood revealed. Space reduces 100 immune-related genes. Stress may cause it. Laneuville suggests another possibility: “Those genes respond to a decrease in gravitational force.”

In microgravity, astronauts’ blood moves from their legs to their torsos and heads. It’s unsettling. Their body reduces fluid by 15% to fix it. That suggests too many immune cells are in this tiny blood.

Laneuville thinks the gene activity reduction eliminates the excess cells. This impacts pathogen response by the immune system.

“The body is telling them, ‘Don’t defend, put your guards down,’” she explains.

This would allow viral and bacterial diseases to spread to astronauts.

Once they arrive, the genes are turned back up and fluid levels normalize. For many genes, this reversal takes weeks rather than a year.

Brian Crucian, a NASA research immunologist who wasn’t involved in the study, said the discovery may help Earth’s immune-compromised.

Consider an old person or a transplant patient. Astronauts and terrestrial medicine have many similarities.

This research may aid long-term Antarctic residents. Crucian says you “run them through difficult travel to a profoundly extreme environment” with these people. They spend a year at a base with 24-hour darkness and daylight. The Antarctic has practically everything except microgravity and radiation.

This study is a promising start, says NYU Abu Dhabi biomedical engineer Jeremy Teo.

Experts warn it will be tougher to bring astronauts back to Earth for rehabilitation or treatment when we send them to the Moon and Mars.

Teo claims extraditing compromised astronauts to Earth is no longer possible. Thus, we must create new immune system defenses for space flight.