The first building elements of organic life, amino acids and carboxylic acids, may have been formed by the collision of solar particles from solar eruptions with vapors in the early Earth’s atmosphere, according to scientists.

In the late 1800s, scientists hypothesized that the origins of life began in a “warm little pond”: a soup of chemicals energized by electricity, heat, and other energy sources that could combine to create organic molecules.

In 1953, when these conditions were recreated in a laboratory at the University of Chicago, twenty distinct amino acids were discovered to have formed.

Life began in a “warm little pond” according to late 1800s biologists.

Vladimir Airapetian, a stellar astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and coauthor of this new paper published in the journal Life, explained that these complex organic molecules can be synthesized from the fundamental components of the early Earth’s atmosphere.

Scientists now believe that 70 years ago, ammonia (NH3) and methane (CH4) were far less abundant than carbon dioxide (CO2) and molecular nitrogen (N2), which require more energy to break down. These gases can still produce amino acids, albeit in much smaller quantities.

Using data from NASA’s Kepler mission, Airapatian, in search of alternative energy sources, proposed a novel concept: energetic particles from our Sun.

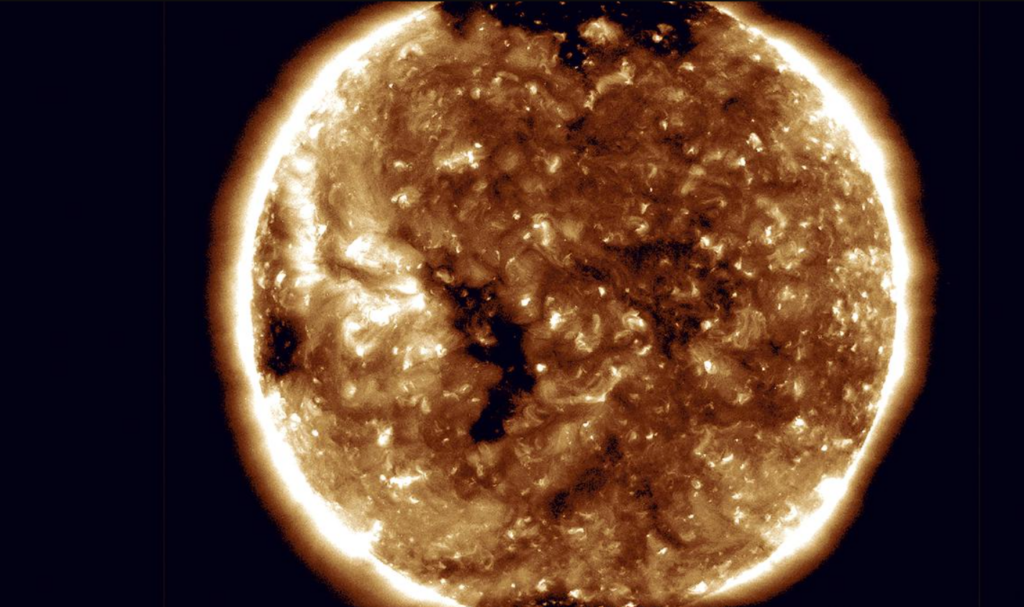

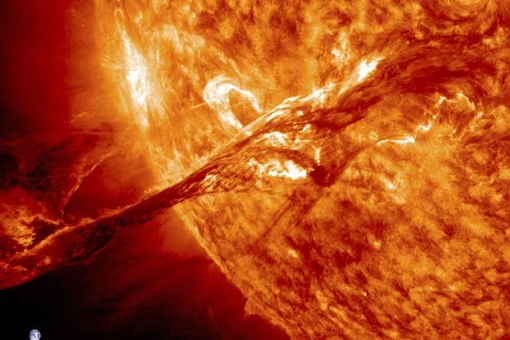

In 2016, Airapetian published a study indicating that during the first 100 million years of Earth’s existence, when the Sun was about 30% dimmer, solar “superflares” – strong eruptions that occur roughly every 100 years today – would have occurred every 3-10 days.

These superflares propel particles at near-light speed, which frequently collide with our atmosphere and initiate chemical reactions.

A Japanese team from Yokohama National University contacted Airapetian.

Dr. Kobayashi, a chemistry professor, was attempting to comprehend how galactic cosmic radiation — particles from beyond our solar system — could have impacted the early Earth’s atmosphere.

To comprehend this, Airapetian, Kobayashi, and their colleagues simulated the early Earth’s atmosphere using a mixture of gases.

They combined carbon dioxide, molecular nitrogen, water, and a variable quantity of methane, which was thought to have been low in the early atmosphere of Earth. They fired the gas mixtures with protons (simulating solar particles) or ignited them with spark discharges (simulating lightning) as a comparison to the experiment conducted at the University of Chicago.

As long as the methane concentration was greater than 0.5%, the protons (solar particles) produced amino acids and carboxylic acids in detectable amounts.

Before any amino acids could form, however, spark discharges (lightning) required a methane concentration of approximately 15%.

“And even at 15% methane, the production rate of amino acids by lightning is a million times less than that of protons,” Airapetian continued. In addition, protons tend to generate more carboxylic acids (a precursor to amino acids) than spark discharges.

These experiments suggested that our youthful, active Sun may have catalyzed the origins of life more readily and possibly earlier than previously believed.