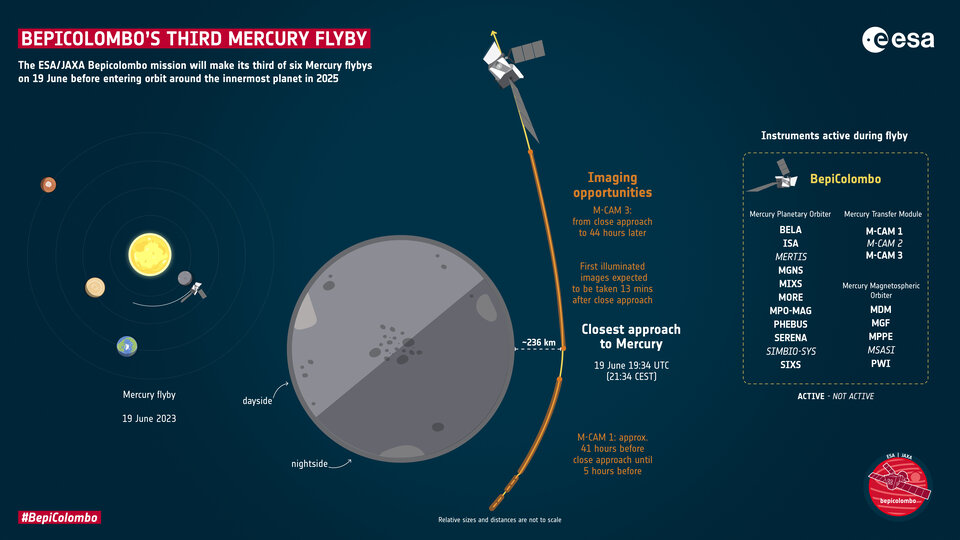

On June 19, the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission will fly near Mercury at 236 km.

The ESA spacecraft operation team is steering BepiColombo through its third of six Mercury gravity assist flybys.

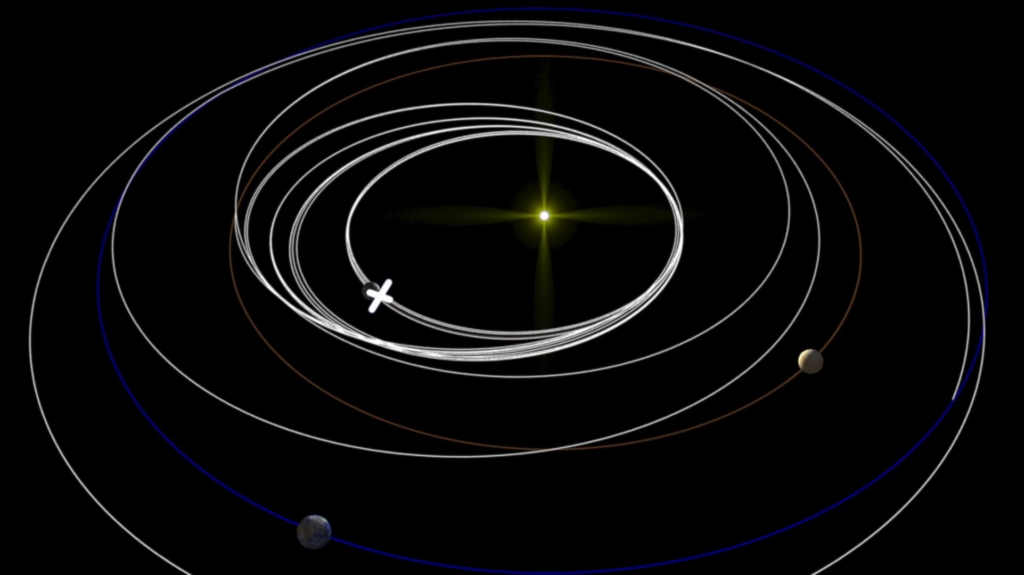

The spacecraft needs the flybys and more than 15,000 hours of hard solar electric propulsion operations to overcome the Sun’s immense gravitational pull and lose enough energy to be caught into Mercury’s orbit in 2025.

Monday’s flyby will be closest at 19:34 UTC (21:34 CEST). BepiColombo will approach Mercury on the night side, thus its monitoring cameras will capture Mercury’s most fascinating features 13 minutes later. 20 June should see the first photos.

Flybys, thrusters

The flyby allows BepiColombo to harness Mercury’s gravity to navigate the inner Solar System.

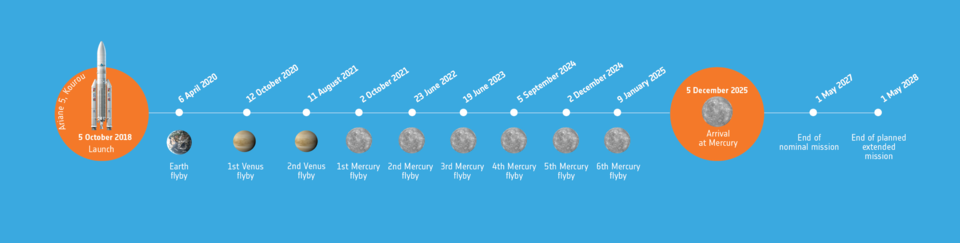

The project launched on an Ariane 5 from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou in October 2018 and is using nine planetary flybys—one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury—to steer into Mercury orbit.

After this flyby, the mission will progressively increase its usage of solar electric propulsion using ‘thrust arcs’ to brake against the Sun’s immense gravitational pull.

Longer thrust arcs are interrupted for navigation and manoeuvre optimization.

Cosmic slingshot

Mercury, the Solar System’s least studied rocky planet, is hard to reach. As BepiColombo approaches the Sun, its enormous gravitational pull accelerates it.

Gravity assist flybys can shift direction with little fuel, but they are difficult.

Flight controllers will steer BepiColombo to pass Mercury at the appropriate distance, angle, and speed. This was calculated years before but must be perfect on the day.

BepiColombo will move 3.6 km/s relative to Mercury when it feels its gravitational pull. ESA flight dynamics specialist Frank Budnik says that’s slightly over half the speed it approached Mercury during the last two flybys.

“This is the point of such events. Since it launched from Earth, our spaceship had too much energy. We’re leveraging Earth, Venus, and Mercury’s gravity to slow down to be grabbed by Mercury.”

Mission control completed the greatest chemical propulsion maneuver on 19 May. The goal was to repair orbital inaccuracies caused by thruster outages during BepiColombo’s one-and-a-half-month slow electric propulsion arc. Without this correction maneuver, BepiColombo would be 24,000 km from Mercury and on the incorrect side of the planet!

The latest maneuver was devised so BepiColombo would pass Mercury at a slightly higher altitude than needed to avoid a collision. The extra margin was a solid gamble and erased prior errors as the spaceship traveled millions of km. BepiColombo will fly over the planet at 236 km (+/-5 km) one week from today.

At close approach, Mercury’s gravitational force will accelerate BepiColombo to 5.4 km/s, although the flyby will lower the spacecraft’s velocity magnitude relative to the Sun by 0.8 km/s and shift its orientation by 2.6 degrees.

Santa Martinez Sanmartin, ESA’s BepiColombo mission manager, says, “This is the first time that the complex solar electric propulsion method is being used to get a spacecraft to Mercury, and it represents a big challenge during the remaining part of the cruise phase.

We have added communications passes with our ground stations to recover faster from thruster disruptions and enhance orbit determination. Due to light signal delays between Earth and the spaceship, communications delays are greater than 10 minutes.

Flight dynamics combines art and science. Spacecraft are not ideal mathematical objects, thus orbits, manoeuvres, and flybys are planned years in advance. Teams always err on the side of caution, factoring in several possibilities for manoeuvres to hone and adjust a spacecraft’s route.

Science tastes

Some equipment will work during the flyby, giving another tantalizing look of Mercury research planned during the main mission. Magnetic, plasma, and particle monitors will take samples before, during, and after closest approach.

This will be the first flyby for the BepiColombo Laser Altimeter (BELA) and Mercury Orbiter Radio-science Experiment (MORE). BELA will only be turned on for functional testing. BELA will measure Mercury’s surface and MORE will study its gravitational field and core once in orbit.

“Collecting data during flybys is extremely valuable for the science teams to check their instruments before the main mission,” says ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist Johannes Benkhoff.

“It also provides a unique opportunity to compare with data collected by NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft during its 2011–2015 mission at Mercury from complementary locations around the planet not usually accessible from orbit. We’re thrilled to get into orbit since our flyby data has already produced fresh research discoveries.

ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) will separate from BepiColombo’s Mercury Transfer Module (MTM) and begin complementary orbits around Mercury in December 2025.

BepiColombo’s monitoring cameras capture flybys when the main science camera is protected.

Unique selfie

BepiColombo will be shadowed by Mercury during closest approach. When BepiColombo is 1840 km away, the spaceship will see the bright planet 13 minutes later.

No closest approach photos will be lit. Mercury’s surface will look best between 13 and 23 minutes following close approach.

Cameras take 1024 × 1024 black-and-white photos. They also catch MTM’s solar array and MPO’s antennae in the foreground due to their spacecraft location. Mercury will show in the top right of M-CAM 3 photos as BepiColombo passes it and go to the bottom left.

The first photographs will be downlinked within two hours of closest approach and released on 20 June afternoon. The nearest photographs should show massive craters, volcanic, and tectonic terrain.